Software Architectural Design - Part 2

Bài đăng này đã không được cập nhật trong 6 năm

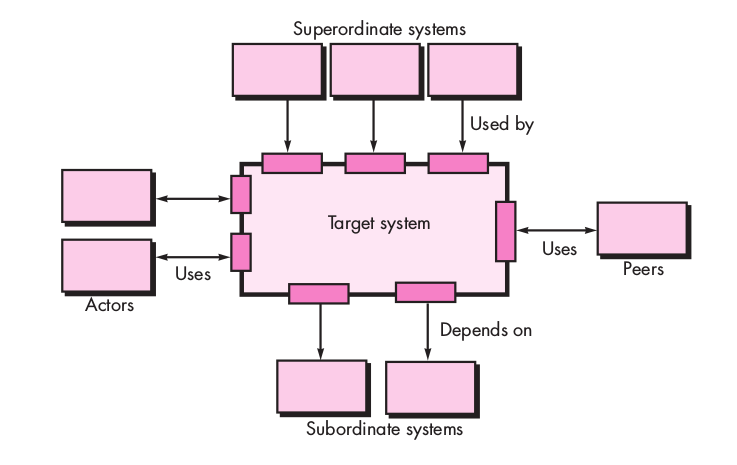

Architectural Context

At the architectural design level, a software architect uses an architectural context di- agram (ACD) to model the manner in which software interacts with entities external to its boundaries.

- Superordinate systems—those systems that use the target system as part of some higher-level processing scheme

- Subordinate systems—those systems that are used by the target system and provide data or processing that are necessary to complete target system functionality.

- Peer-level systems—those systems that interact on a peer-to-peer basis (i.e., information is either produced or consumed by the peers and the target system.

- Actors—entities (people, devices) that interact with the target system by producing or consuming information that is necessary for requisite processing.

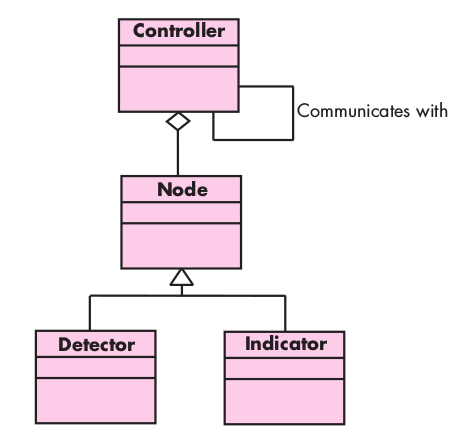

Archetypes

An archetype is a class or pattern that represents a core abstraction that is critical to the design of an architecture for the target system. In general, a relatively small set of archetypes is required to design even relatively complex systems. The target sys- Archetypes are the abstract building blocks of an architectural design. tem architecture is composed of these archetypes, which represent stable elements of the architecture but may be instantiated many different ways based on the behavior of the system. In many cases, archetypes can be derived by examining the analysis classes de- fined as part of the requirements model.

- Node. Represents a cohesive collection of input and output elements of the home security function. For example a node might be comprised of (1) various sensors and (2) a variety of alarm (output) indicators.

- Detector. An abstraction that encompasses all sensing equipment that feeds information into the target system.

- Indicator. An abstraction that represents all mechanisms (e.g., alarm siren, flashing lights, bell) for indicating that an alarm condition is occurring.

- Controller. An abstraction that depicts the mechanism that allows the arming or disarming of a node. If controllers reside on a network, they have the ability to communicate with one another.

Analyzing Architectural Design

- Collect scenarios.

- Elicit requirements, constraints, and environment description.

- Describe the architectural styles/patterns that have been chosen to address the scenarios and requirements:

- module view

- process view

- data flow view

- Evaluate quality attributes by considered each attribute in isolation.

- Identify the sensitivity of quality attributes to various architectural attributes for a specific architectural style.

- Critique candidate architectures (developed in step 3) using the sensitivity analysis conducted in step 5.

Architectural Complexity

A useful technique for assessing the overall complexity of a proposed architecture is to consider dependencies between components within the architecture. These de- pendencies are driven by information/control flow within the system. Zhao [Zha98] suggests three types of dependencies:

- Sharing dependencies represent dependence relationships among consumers who use the same resource or producers who produce for the same consumers.

- Flow dependencies represent dependence relationships between producers and consumers of resources.

- Constrained dependencies represent constraints on the relative flow of control among a set of activities.

ADL

- Architectural description language (ADL) provides a semantics and syntax for describing a software architecture

- Provide the designer with the ability to:

- decompose architectural components

- compose individual components into larger architectural blocks and

- represent interfaces (connection mechanisms) between components.

General Mapping Approach

- Isolate incoming and outgoing flow boundaries; for transaction flows, isolate the transaction center

- Working from the boundary outward, map DFD transforms into corresponding modules

- Add control modules as required

- Refine the resultant program structure using effective modularity concepts

- Isolate the transform center by specifying incoming and outgoing flow boundaries

- Perform "first-level factoring.”

- The program architecture derived using this mapping results in a top-down distribution of control.

- Factoring leads to a program structure in which top-level components perform decision-making and low-level components perform most input, computation, and output work.

- Middle-level components perform some control and do moderate amounts of work.

- Perform "second-level factoring."

Reference: Software Engineering A Practitioner's Approach (7th Ed.) ~ Roger S. Pressman

All rights reserved