Pattern-Based Design

Bài đăng này đã không được cập nhật trong 5 năm

What is it?

Pattern-based design creates a new application by finding a set of proven solutions to a clearly delineated set of problems. Each problem and its solution is escribed by a design pattern that has been cataloged and vetted by other software engineers who have encountered the problem and implemented the solution while designing other applications. Each design pattern provides you with a proven approach to one part of the problem to be solved.

Who does it?

A software engineer examines each problem encountered for a new application and then attempts to find a relevant solution by searching one or more patterns repositories.

Why is it important?

Have you ever heard the phrase “reinventing the wheel”? It happens all the time in software development, and it’s a waste of time and energy. By using existing design patterns, you can acquire a proven solution for a specific problem. As each pattern is applied, solutions are integrated and the application to be built moves closer to a complete design.

What are the steps?

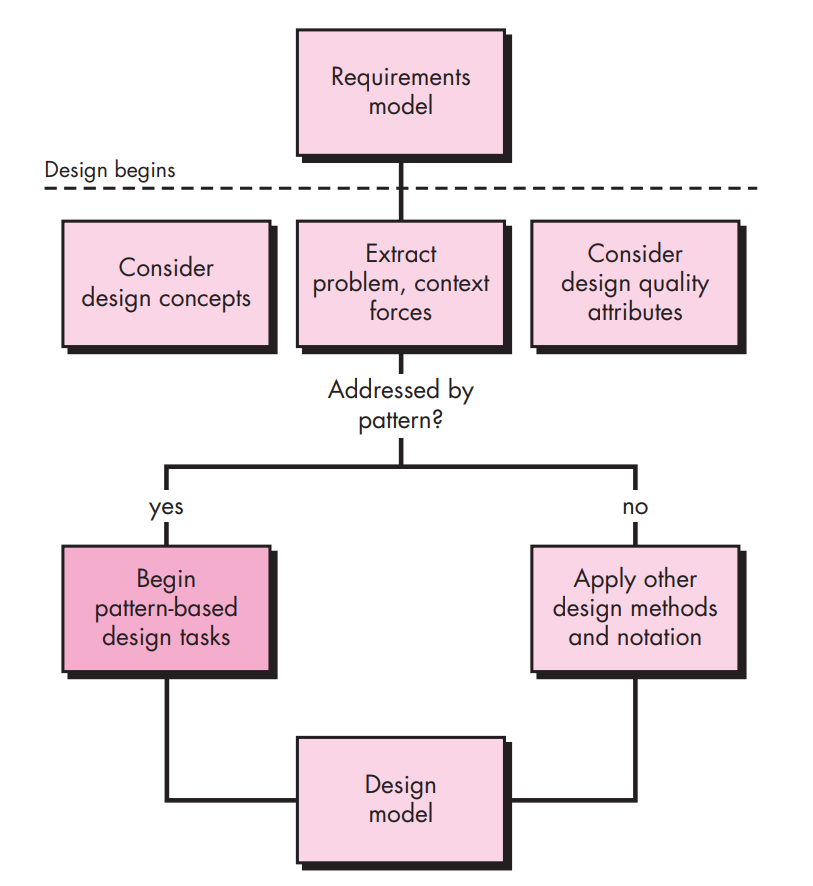

The requirements model is examined in order to isolate the hierarchical set of problems to be solved. The problem space is partitioned so that subsets of problems associated with specific software functions and features can be identified. Problems can also be organized by type: architectural, componentlevel, algorithmic, user interface, etc. Once a subset of problems is defined, one or more pattern repositories are searched to determine if an existing design pattern, represented at an appropriate level of abstraction, exists. Patterns that are applicable are adapted to the specific needs of the software to be built. Custom problem solving is applied in situations for which no patterns can be found.

What is the work product?

A design model that depicts the architectural structure, user interface, and component-level detail is developed. How do I ensure that I’ve done it right? As each design pattern is translated into some element of the design model, work products are reviewed for clarity, correctness, completeness, and consistency with requirements and with one another.

Kinds of Patterns

- Architectural patterns describe broad-based design problems that are solved using a structural approach.

- Data patterns describe recurring data-oriented problems and the data modeling solutions that can be used to solve them.

- Component patterns (also referred to as design patterns) address problems associated with the development of subsystems and components, the manner in which they communicate with one another, and their placement within a larger architecture

- Interface design patterns describe common user interface problems and their solution with a system of forces that includes the specific characteristics of end-users.

- WebApp patterns address a problem set that is encountered when building WebApps and often incorporates many of the other patterns categories just mentioned.

- Creational patterns focus on the “creation, composition, and representation of objects, e.g.,

- Abstract factory pattern: centralize decision of what factory to instantiate

- Factory method pattern: centralize creation of an object of a specific type choosing one of several implementations

- Structural patterns focus on problems and solutions associated with how classes and objects are organized and integrated to build a larger structure, e.g.,

- Adapter pattern: 'adapts' one interface for a class into one that a client expects

- Aggregate pattern: a version of the Composite pattern with methods for aggregation of children

- Behavioral patterns address problems associated with the assignment of responsibility between objects and the manner in which communication is effected between objects, e.g.,

- Chain of responsibility pattern: Command objects are handled or passed on to other objects by logic-containing processing objects

- Command pattern: Command objects encapsulate an action and its parameters

Frameworks

Patterns themselves may not be sufficient to develop a complete design. In some cases it may be necessary to provide an implementation-specific skeletal infrastructure, called a framework, for design work. That is, you can select a “reusable miniarchitecture that provides the generic structure and behavior for a family of software abstractions, along with a context . . . which specifies their collaboration and use within a given domain” [Amb98].

A framework is not an architectural pattern, but rather a skeleton with a collection of “plug points” (also called hooks and slots) that enable it to be adapted to a specific problem domain. The plug points enable you to integrate problem-specific classes or functionality within the skeleton. In an object-oriented context, a framework is a collection of cooperating classes.

Describing a Pattern

- Pattern name: describes the essence of the pattern in a short but expressive name

- Problem : describes the problem that the pattern addresses

- Motivation : provides an example of the problem

- Context : describes the environment in which the problem resides including application domain

- Forces : lists the system of forces that affect the manner in which the problem must be solved; includes a discussion of limitation and constraints that must be considered

- Solution : provides a detailed description of the solution proposed for the problem

- Intent : describes the pattern and what it does

- Collaborations : describes how other patterns contribute to the solution

- Consequences : describes the potential trade-offs that must be considered when the pattern is implemented and the consequences of using the pattern

- Implementation : identifies special issues that should be considered when implementing the pattern

- Known uses : provides examples of actual uses of the design pattern in real applications

- Related patterns : cross-references related design patterns

Thinking in Patterns

Shalloway and Trott [Sha05] suggest the following approach that enables a designer to think in patterns:

- Be sure you understand the big picture—the context in which the software to be built resides. The requirements model should communicate this to you.

- Examining the big picture, extract the patterns that are present at that level of abstraction.

- Begin your design with ‘big picture’ patterns that establish a context or skeleton for further design work.

- “Work inward from the context” [Sha05] looking for patterns at lower levels of abstraction that contribute to the design solution.

- Repeat steps 1 to 4 until the complete design is fleshed out.

- Refine the design by adapting each pattern to the specifics of the software you’re trying to build.

Design Tasks

- Examine the requirements model and develop a problem hierarchy.

- Determine if a reliable pattern language has been developed for the problem domain.

- Beginning with a broad problem, determine whether one or more architectural patterns are available for it.

- Using the collaborations provided for the architectural pattern, examine subsystem or component level problems and search for appropriate patterns to address them.

- Repeat steps 2 through 5 until all broad problems have been addressed.

- If user interface design problems have been isolated (this is almost always the case), search the many user interface design pattern repositories for appropriate patterns.

- Regardless of its level of abstraction, if a pattern language and/or patterns repository or individual pattern shows promise, compare the problem to be solved against the existing pattern(s) presented.

- Be certain to refine the design as it is derived from patterns using design quality criteria as a guide.

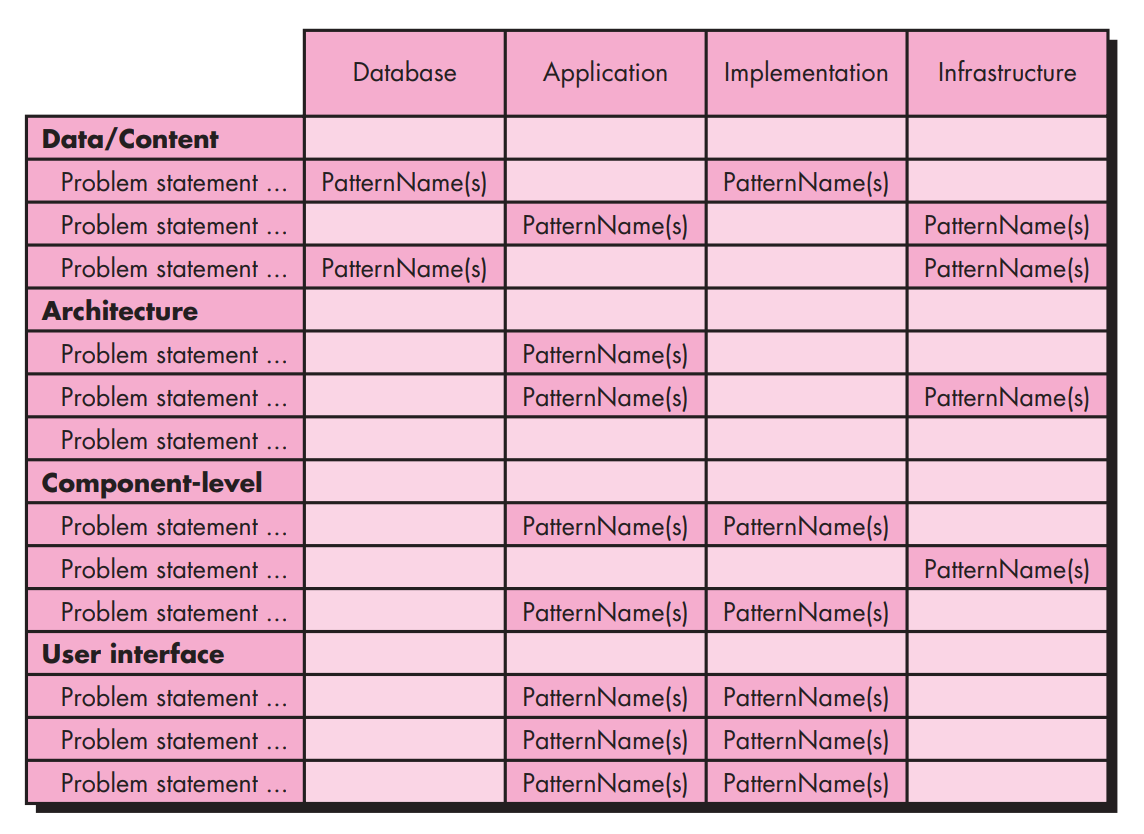

Pattern Organizing Table

Common Design Mistakes

Pattern-based design can make you a better software designer, but it is not a panacea. Like all design methods, you must begin with first principles, emphasizing software quality fundamentals and ensuring that the design does, in fact, address the needs expressed by the requirements model.

A number of common mistakes occur when pattern-based design is used. In some cases, not enough time has been spent to understand the underlying problem and its context and forces, and as a consequence, you select a pattern that looks right but is inappropriate for the solution required. Once the wrong pattern is selected, you refuse to see your error and force-fit the pattern. In other cases, the problem has forces that are not considered by the pattern you’ve chosen, resulting in a poor orerroneous fit. Sometimes a pattern is applied too literally and the required adaptations for your problem space are not implemented.

Reference: Software Engineering A Practitioner's Approach (7th Ed.) ~ Roger S. Pressman

All rights reserved