Linux: Processes

Bài đăng này đã không được cập nhật trong 6 năm

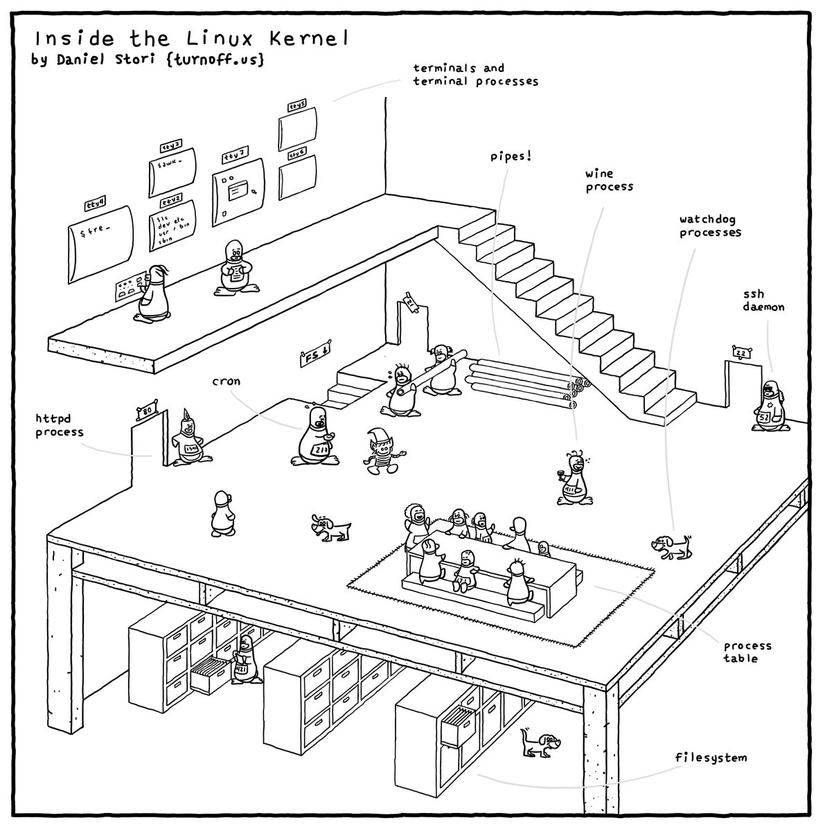

Processes are at the core of every application execution. Obviously, the understanding of process is vital for application development and devops. This article attempts to cover the basics about Linux processes, it's components and basic operations. It can be used as a reference and / or cheatsheet for Linux process basics, rather than a guide to understand Linux processes from the scratch. Let's get started!

Process

A process is a program that is currently loaded in the memory, and is in any valid phase of execution. A process is constructed of program instructions, data read from files, other processes and / or I/O.

Processes can be distinguished into,

- Foreground process: Foreground processes are usually associated with an I/O (e.g. terminal session), and can often be interacted with.

- Background process: Background process (also known as daemon) are processes not associated with a terminal session. These processes are often started automatically by the OS, and often contains service management payloads.

Process Components

- Process consists of an address space and a set of data structures within the kernel

- Address space is a set of memory pages that the kernel marked for the process's use

- Pages are units in which memory is managed (usually 4 or 8 KiB)

- Page contains,

- Executing code and libraries

- It's stack

- Other info

- Virtual address space of a process is laid out randomly in physical memory and tracked by the kernel's page tables

- Kernel's internal data structure records various information about each process. Some significant info includes,

- address space map

- current status (e.g. running, sleeping, stopped)

- execution priority

- resource usage (e.g. CPU, memory)

- files and network ports opened

- signal mask

- process owner

- Thread is an execution context within a process. A process has at least one thread

- Each thread has its own stack and CPU context, but operates within parent process's address space

- One process's threads may simultaneously run on different cores

- PID

- Unique ID of each process

- Assigned in the order of creation (e.g. PID 1 is started before all other processes in a system)

- Namespace restricts processes' ability to see and affect each other

- PPID

- Linux does not create a new process, instead, an existing process is cloned and the cloned process is assigned the target payload

- Parent process is the process from where a process is cloned

- Parent processes' ID is PPID

- When parent dies, init or systemd becomes the new parent

- UID and EUID (Real and Effective UID)

- Process's UID is it's creator user account's UID

- To be more specific, copy of parent process's UID

- EUID

- An extra UID that determines what resources and files a process has access to at any given moment

- For most process, UID and EUID are the same

- Processes of which permission has been changed (via

setuid), have different EUID - UID and EUID maintains identity and permissions consecutively

- A Saved UID is initial EUID

- FSUID is a nonstandard parameter used to control filesystem permissions

- Process's UID is it's creator user account's UID

- GID and EGID (Real and Effective GID)

- GID is the group identifier

- EGID is identical to EUID and can be upgraded by

setgidprogram - Identical to UID, kernel maintains a saved GID

- A process may belong to many groups

- Process access management uses EGID and a supplemental group list

- Niceness

- A value that specifies how nice a process will be (how much resource it's capable of releasing) to other users of the system

- A process' scheduling priority determines how much CPU time it receives

- Kernel determines scheduling priority by,

- using a dynamic algorithm that takes into account how much CPU time a process recently consumed and the length of time it has been waiting to run

- Nice value, that is administratively set

- Control Terminal

- Most non-daemon (foreground) processes have an associated control terminal

- The control terminal determines the default linkage for the standard output, standard input and standard error channels.

- Control terminal also distributes signals to processes in response to the keyboard events

Process Life Cycle

To create a new process, a process copies itself using a fork system call (technically Linux uses clone, which is a superset of fork)

Newly generated process has its own PID and accounting information.

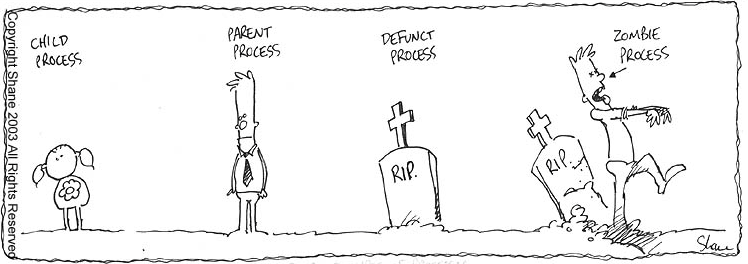

When a process dies or killed, before a dead process is allowed to disappear completely, kernel requires that it's death be acknowledged by it's parent, which the parent does with a call to wait. Parent receives a copy of child's exit code.

When parent dies before child, init system becomes the parent, and performs the wait needed to get rid of them when they die.

Signals

Signals are process level interrupt requests. There are about thirty signals for various purposes. The primary usage are as follows.

- Signals can be sent among processes as a means of communication

- They can be sent by the terminal driver to kill, interrupt or suspend (e.g. <Control-C> and <Control-Z> key press)

- Can be sent by administrator (with

kill) to achieve various ending - Can be sent by the kernel when a process commits an infraction (e.g. division by zero)

- Can be sent by the kernel to notify an event (e.g. death of a child process, availability of data on an I/O channel)

When a signal is received, one of two things can happen.

- If process has a designated handler for that particular signal, it is called with context information

- Else, kernel takes default action on behalf of the process

- For some signal,default action may include,

- terminating the process

- terminating and generating core dump (Core Dump is a copy of a process's memory image)

- For some signal,default action may include,

A signal can be ignored or blocked. A blocked signal is queued for delivery, and is delivered once unblocked

Some significant signal includes,

- HUP: HangUP

- INT: INTerrupt

- QUIT: QUIT

- KILL: KILL

- BUS: BUS error

- SEGV: SEGmentation fault

- TERM: software TERMination

- STOP: STOP

- TSTP: keyboard SToP

- WINCH: WINdow CHanged

- USR1: USeR defined #1

- USR2: USeR defined #2

Other signals are mostly obscure errors, of which the default handling is to terminate with a core dump

BUS and SEGV are common error signals

KILL and STOP cannot be caught, blocked or ignored.

- KILL destroys the process

- STOP suspends execution until a CONT is received

- CONT can be caught or ignored, but not blocked

TSTP is a soft version of STOP, that can be described as a stop request

- Example: Terminal <Control-Z> (apps usually clean up their state and send themselves a STOP to complete the stop operation)

KILL is unblockable and terminates a process at kernel level. Process can never receive or handle this signal

INT is sent by terminal driver when user presses <Control-C>.

- It's a request to terminate current operation

- If not caught, applications are killed

- Programs with interactive CLI should stop what they're doing, clean up, and wait for user input again

TERM is a request to terminate execution completely. It's expected that the receiving process will clean up its state and exit

HUP has two common interpretations

- It's understood as a reset request by many daemons. If daemon is capable of rereading its configuration file and adjusting to changes without restarting, a HUP generally trigger this behavior.

- HUP are sometimes generated by the terminal driver in an attempt to clean up the processes attached to a particular terminal.

QUIT is similar to TERM, except that it defaults to producing a core dump if not caught.

USR1 and USR2 are user defined, and it's up to the program to ignore or execute an action when received

Relevant Utilities

kill

- Used to terminate a process

killcan send any signal- By default, it sends a TERM

- KILL sometimes may not work if a process is engaged with some misbehaving I/O lock.

- Example: To send a KILL signal to a process,

kill -9 processx

killall

- Used to kill processes by name

- Example:

sudo killall httpd

pkill

- Searches for processes by name (or other attributes, such as EUID) and sends the specific signal.

- Example: To send TERM signal to all processes running as user jerry,

sudo pkill -u jerry

Process and Thread States

When a process is running, often threads must wait for kernels for some background work to be completed (e.g. file data access). In the meantime, thread may enter a short term sleep state. Other threads may however continue to run.

- A thread is reported as sleeping, when all it's threads are asleep.

- Interactive shells and system daemons spend most of the time sleeping, waiting for terminal input or network connections

- Since a sleeping thread is effectively blocked until its request has been satisfied, its process generally receives no CPU time unless it receives a signal or a response to one of its I/O requests.

- Some operations can cause processes or threads to enter an uninterruptible sleep state. This state is usually transient and is not observed in

ps(denoted byDin STAT column)- Some misbehaving event may cause this state to persist. Since processes in this state cannot be roused even to service a signal, they cannot be killed. To get rid of them, the issue must be fixed or a reboot is necessary.

- Zombie processes are the ones that have finished execution but their status have not yet been collected by their parent process (or by init system).

Process Monitoring

-

psis primarily used for process monitoring -

Example:

ps auxUSER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND root 1 0.0 0.0 185456 5024 ? Ss Mar04 0:03 /sbin/init splash root 1102 0.0 0.0 30856 2544 ? Ss Mar04 0:00 /usr/sbin/cron -f mysql 1543 0.0 0.9 1895680 153540 ? Ssl Mar04 3:38 /usr/sbin/mysqld ... -

psprovides a static snapshot -

ps auxprovides an overview of all processes running on a system. Here are some flags commonly used withps:l: shows long output formata: shows all processesx: shows processes even without control terminalu: provides user oriented output formatw: Longer output, (wwfor even longer)

-

Command names in brackets are not commands. These are kernel threads scheduled as processes.

-

ps auxOutput Format- USER: Process owner's username

- PID

- %CPU

- %MEM

- VSZ: Virtual size of the process

- RSS: Resident set size (number of pages in memory)

- TTY: Control terminal ID

- STAT: Current process status

-

R: Runnable -

S: Sleeping (less than 20 seconds) -

Z: Zombie -

D: In uninterruptible sleep -

T: Traced or stopped -

W: Processed is sWapped out -

<: Higher than normal priority -

N: Lower than normal priority -

L: Some pages are locked in core -

s: Process is a session leader -

l: Process is multi-threaded

-

- TIME: CPU time the process has consumed

- COMMAND: Command name and arguments ( program can modify, so not necessarily accurate )

- NI: Niceness

- PPID

- WCHAN: Wait CHANnel (type of resource on which the process is waiting)

-

PID Extraction

ps aux | grep sshdpidof /usr/sbin/sshdpgrep sshd

For the example above, let's investigate the last process indexed by the ps.

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

mysql 1543 0.0 0.9 1895680 153540 ? Ssl Mar04 3:38 /usr/sbin/mysqld

The information yielded by ps aux indicates that a command /usr/sbin/mysqld

was invoked by mysql user on March 4th. The process was started with PID

1543, which is currently utilizing 0% CPU and 0.9% memory, with a

residential memory of 153540 pages and virtual memory size of 1895680.

So far, the process consumed 3 minutes and 38 seconds (TIME 3:38) of CPU time. The

process is a daemon since there is no associated terminal (TTY ?). The

daemon is a multi-threaded (STAT l) session initiator (STAT s) and

is currently in sleeping state (STAT S).

Interactive Monitoring

topis a sort of real time version ofpsthat gives regularly updated, interactive summary of processes and their resource usagehtopis more feature rich alternativetopalso accepts input from the keyboard to send signals and renice processes- On multicore systems, CPU usage is an average of all the cores in the system

NICE and RENICE

Niceness of a process is a numeric hint to the kernet about how it should be treated in relation to other processes contending for the CPU.

- Lower niceness == Higher priority

- Higher niceness == Lower priority

- In Linux, the allowable niceness value range is between -20 to +19

So far we went through the basic concepts, operations and utilities related to Linux process monitoring and management. Although, a process, in it's

entirety, has a lot more attributes than what we discussed, it is enough for the basic understanding and and majority of the process management

operations performed by developers and devops. Enjoy!

References

- Linux Bible by Christopher Negus

- UNIX and Linux System Administration Handbook

- http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man1/ps.1.html

- http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man1/top.1.html

- Comics

All rights reserved