Domain-specific Language Implementation Patterns (Pt. 2): Syntactic Analyzer in DSL

Bài đăng này đã không được cập nhật trong 7 năm

3. Syntactic Analyzer

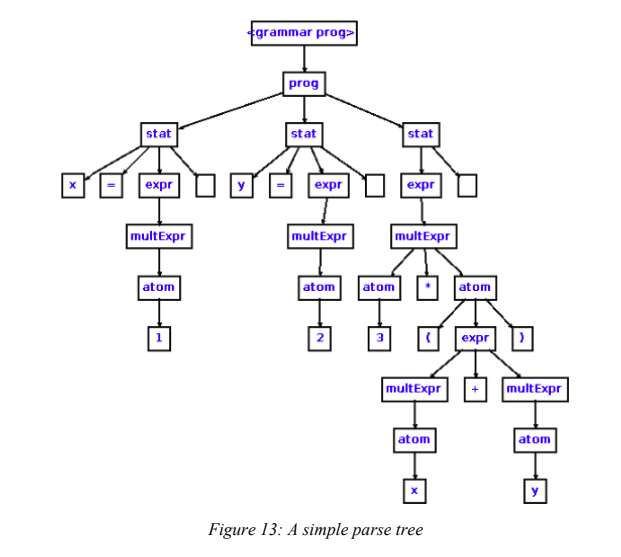

The next step after lexing is parsing. Parsers are also recognizer programs, but operate on a larger scale than lexers. While lexers recognize tokens – the smallest structured part of a language – parsers feed on those tokens and build syntactic representations. These representations, previously described as IRs, are processed versions of the input text. The purpose of IRs is to allow other programs in the pipeline to traverse them easily, since traversing and locating symbols in text is both inefficient and inaccurate. IRs usually have a collection of nodes or elements, which can be used to stored information (metadata) about the nodes themselves. A program in the pipeline, when needed, can go directly into a specific node and fetch its metadata for processing. There are several kinds of IRs, based on the type of application, a suitable kind of representation can be picked. For source code presentation programs, like syntax-highlighting editors, they often store IRs as parse trees, which contain not only the input itself in each node, but records of the rules used to recognize the input. In other words, parse trees store almost everything that is inside the original text input, including even whitespace characters like spaces, tabs and newlines. This obviously provides applications like syntax-highlighters with more necessary information to work with.

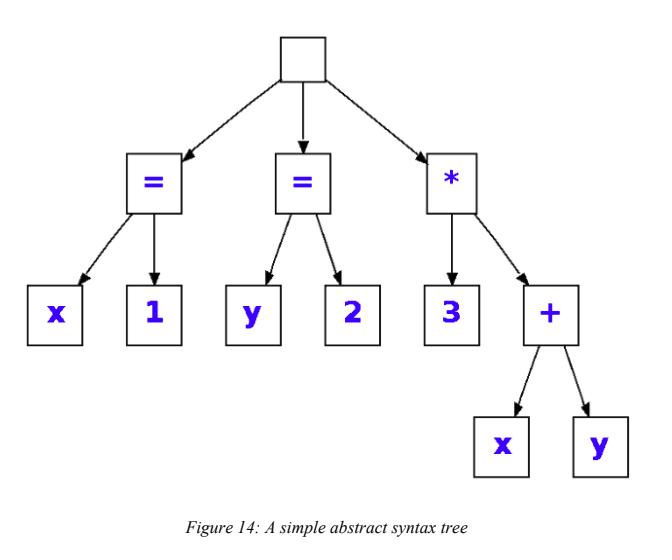

Parser trees are sometimes called concrete syntax trees, because they retain concrete information of the original input, i.e. all characters. For other source code analyzer programs, like compilers, IRs are often abstract syntax trees (ASTs). Compilers only need to care about the value of each element and not how spaced out elements are to each other. This is why for implementing a programming language, the most suitable IR implementation is AST. An abstract syntax tree, as the name suggests, is a tree-like model that describes the abstract values of the text input. For an expression like this:

3 * ( (x + y ))

An AST for this expression only stores the crucial tokens: operations („*‟ and „+‟) and values (3, x, y) and the order of operations, and not the parentheses or space characters.

There are also several types of ASTs, based on the need of the implementing application; the more demanding it is, the more complicated types of ASTs required. The simplest kind of AST is Homogeneous AST, which uses a single data structure to represent all nodes. In this type of AST, each node is derived from a token; and since each token contains enough information about its type and value, nodes don‟t need to store any other information but the tokens themselves. To handle child nodes, each node can optionally store a flat list of child nodes, or normalized child representation. An implementation of a homogeneous AST in Java might look like this:

public class ASTNode {

Token token; // the token that this node derives from

List<ASTNode> children; // a normalized list of children of this node

// constructors...

// most used actions on a node are value retrieval and type retrieval

public int getType() { return token.GetType(); }

public int getValue() { return token.GetValue(); }

public object[] getChildren { return children.ToArray(); }

public void addChild(ASTNode node) { children.add(node); }

}

Normalized Heterogeneous AST is an extension to Homogeneous AST, in that it allows multiple node types, while keeping the normalized child list. The gain of this AST type over Homogeneous AST is that it allows implementers to store additional data for uses in later stages. A normalized heterogeneous AST also keeps a flat list of child nodes, which makes it easy to traverse nodes and their children. Because a normalized heterogeneous AST node is just a homogeneous AST node with extra data, in practice, the class for Normalized Heterogeneous AST can use Homogeneous AST as base class. For example, to build an expression node, the Java class of that might be:

public abstract class ExpressionNode extends ASTNode {

int evalType; // data type of the evaluated value

public int GetEvalType() { return evalType; }

// constructors...

}

In this example, ExpressionNode derives from ASTNode because it represents an AST node but with extra information, i.e. the evaluation type. Addition Node, which represents an add operation, use ExpressionNode as base class because an arithmetic operation is an expression. The left and right operand should be compatible in types. The evaluation type of 1 + 1 should be integer. The evaluation type of 2.3 + 1 should be floating-point, and so on.

The next iteration of Normalized Heterogeneous AST is Irregular Heterogeneous AST. The latter one only differs in that the flat children list is now named fields. This results in overall more readable and less error-prone code. So instead of referring to the left and right operand in the previous example as children[0] and children[1], they can be referred to as leftOperand and rightOperand, which is why this pattern is preferable for most AST implementations.

public class AdditionNode extends ExpressionNode {

// named fields instead of flat child list

ExpressionNode leftOperand;

ExpressionNode rightOperand;

public AdditionNode(ExpressionNode leftOperand, Token addOperator, ExpressionNode rightOperand) {

super(addOperator);

this.leftOperand = leftOperand;

this.rightOperand = rightOperand;

}

public int getEvalType() { return

TypeHelpder.getBestTypeCase(leftOperand, rightOperand);

}

}

This implementation, although simple, has been the standardized implementation for abstract syntax trees. With minimal data inside, all can be retrieved from the grammar, there are tools that can automatically generate AST-related classes.

(To be continue)

All rights reserved